Induction of Labour

This page gives you information about induction of labour. It also includes the benefits, risks and alternatives and the process as a whole.

On this page

-

What is induction of labour?

-

Deciding whether to have an IOL

-

Possible risks

-

What happens before an induction

-

Induction of Labour Workshop

-

What happens during an induction?

-

Monitoring your baby

-

Examinations

-

Step 1: Preparing your cervix

-

Mechanical

-

Hormonal

-

What happens next?

-

Step 2: Breaking your waters

-

Step 3: Hormone drip

-

Outpatient IOL - spending time at home during an induction

-

What happens during an outpatient induction?

-

Can I still give birth at the Birth Centre?

-

How long does an induction take?

-

What to do on the day of induction

-

During your stay, please let your midwife know immediately if:

-

What to bring with you into hospital

-

The next steps if the induction does not work

-

Further information

What is induction of labour?

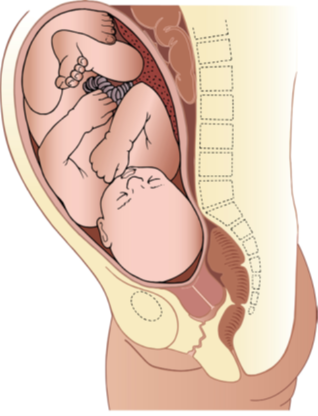

Labour is a natural process that usually starts on its own between 37 and 42 weeks of pregnancy and leads to the birth of your baby.

During pregnancy, your baby is surrounded by a fluid-filled membrane (sac), which protects your baby as it grows in the uterus (womb). The fluid inside the membrane is called amniotic fluid (your waters).

Towards the end of your pregnancy, the cervix (neck of the womb) softens and shortens. This is called the ‘ripening of the cervix’ and can occur over days or weeks.

Before or during labour, your sac of amniotic fluid ruptures. This is known as ‘your waters breaking’.

During labour your cervix dilates (opens) and your womb contracts to push your baby down and out of the womb.

Induction of labour (IOL) is a medical intervention intended to start labour.

Your midwife or doctor might advise you to have an induction if they think that you or your baby’s health is likely to benefit from shortening the length of your pregnancy.

On average labour is induced in 3 to 4 out of every 10 pregnancies across the country. These figures were taken from NHS Digital 2022 and the Gloucestershire figures are similar.

There are many reasons why IOL is offered or advised and the timing will depend on this reason. Studies have shown that IOL after 39 weeks does not increase the risk of needing a caesarean.

The most common reasons for IOL include:

- To reduce the risk of stillbirth if your pregnancy is lasting longer than 41 to 42 weeks (called ‘overdue’ or ‘postdates’).

- To reduce the risk of infection if your waters have broken but labour has not started.

- Because your baby’s movements have changed or there are other concerns about your baby’s wellbeing.

- Pregnancy concerns such as high blood pressure and/or protein in the urine (pre-eclampsia) or gestational diabetes.

Deciding whether to have an IOL

Your doctor or midwife will explain to you the reason why they are recommending or offering an IOL. It is your choice whether to go ahead with an induction.

While making your decision about IOL you may find it helpful to ask yourself the questions in the BRAIN tool below. Doing this may help when you talk to your midwife or doctor.

Benefits: What are the benefits of induction for me and my baby?

Risks: What are the specific risks of induction for me?

Alternatives: What are the alternatives to IOL?

Intuition: How do I feel? What do my instincts tell me?

Nothing: What if I decide to do nothing for now and wait and see? What will happen next?

If you choose not to be induced or to put off your induction, we will make an individualised plan with you.

You could discuss the option of some extra appointments at the hospital, including an ultrasound scan to assess the amount of fluid around your baby and monitoring your baby’s heartbeat. This can help to tell you how your baby is at the time but unfortunately cannot predict or avoid problems that might happen suddenly. Also, a scan cannot predict the risk of a stillbirth.

If you choose to watch and wait, please contact the Maternity Unit as soon as possible on 0300 422 5531 if you have any concerns about your baby’s wellbeing or if you change your mind and would like an induction.

Possible risks

The following points outline the risks of having IOL:

- Tachysystole and hyperstimulation. This means over-contracting of the womb which could cause distress to you and/or your baby with some methods of induction (Propess® pessary or Prostin® tablet). A medication (terbutaline) can be given, by injection, to relax the womb.

- Women who have an induced labour tend to give lower birth satisfaction scores compared to women who spontaneously labour. Inductions are also associated with a longer hospital stay due to the need to remain in hospital for the induction.

- Induced labours are reported as feeling more painful than spontaneous labours. They are also associated with a higher likelihood of regional anaesthesia use (epidural).

- The induction might be unsuccessful.

What happens before an induction

Membrane sweep

In the days before an IOL, you might be offered a membrane sweep which may help you go into labour.

A membrane sweep involves your midwife or doctor performing an internal examination. They will place a finger into your cervix and make a circular, sweeping movement to separate the membranes that surround the baby or they may massage your cervix. The membrane sweep may cause discomfort, pain or light bleeding but will not harm your baby or increase the chance of you or your baby getting an infection.

You may be offered more than one membrane sweep.

Membrane sweeping is not recommended if your membranes have ruptured (waters broken).

Induction of Labour Workshop

You will be offered the opportunity to book onto our Induction of Labour Workshop. These take place via Microsoft Teams at 6:00pm every Monday. The workshop will allow you to find out more about the induction process and ask any questions you may have.

What happens during an induction?

The induction process needs to happen gradually, so it is common for it to take 2 or 3 days (can be up to 5 days) from the start of the induction to the birth of your baby.

The basic steps are:

- Step 1: Prepare or soften (‘ripen’) the cervix.

- Step 2: Break the bag of waters around your baby (artificial rupture of membranes - ‘ARM’).

- Step 3: Stimulate contractions with an oxytocin hormone drip into a vein in your arm.

Monitoring your baby

Before the induction process is started, we recommend monitoring your baby’s heartbeat for 30 minutes. Two monitoring pads will be positioned on your bump and held in place using wide elastic bands. The monitoring pads are attached to a cardiotocograph (CTG) machine, which records your baby’s heart rate and any contractions you may be experiencing.

Examinations

The midwife or doctor will usually offer a vaginal examination at the start of the induction. Further vaginal examinations will then be offered at a few points throughout the induction process to check how prepared your cervix is for labour. This includes assessing how soft and stretchy your cervix is, how open it is, how long (‘effaced’) it is and how low down is your baby’s head.

If your cervix is ‘ready for labour’ (this is more likely if you have had vaginal births before), you may be ready to proceed directly to step 2 and have your waters broken.

If your cervix is not ready for your waters to be broken, there are a variety of methods that can be used to prepare the cervix. The options available will depend on your individual circumstances and preferences.

Step 1: Preparing your cervix

Your doctor or midwife will talk to you about your options for where this first step can take place. This may be on the labour ward or antenatal ward (for women having or who have had complications in their pregnancy), depending on the reason for your induction.

You may have the option of starting your induction in hospital then going home until the first step is complete rather than remaining in hospital (this is called ‘outpatient induction of labour’).

There are 2 approaches to preparing the cervix.

Mechanical

Cook’s Balloon Catheter:

A thin flexible tube is inserted through the cervix with or without the use of a speculum. Two balloons sit at the top and bottom of the cervix and inflate with sterile water to about the size of a golf ball. The flexible tube and balloons can remain in place for 12 to 24 hours although the balloons and tube may fall out before this time as the cervix dilates. There are no medicines involved. This option is intended to help your cervix release hormones that will naturally ripen the neck of your womb.

Risks

- The tube could be uncomfortable to insert.

- There is a higher likelihood of needing an oxytocin drip to start and maintain contractions.

- There is a small risk of cord prolapse or pushing the baby’s head up and out of the pelvis with the balloon.

Benefits

- Low risk of hyperstimulation or scar rupture if you are planning a Vaginal Birth After Caesarean (VBAC).

- Can be used more widely for outpatient induction. This is when you go home after the treatment and do not need to stay overnight in hospital.

Hormonal

Propess®:

This is a vaginal pessary (10mg dinoprostone) which continually releases a low dose of hormone to prepare your cervix for labour. The pessary looks like a small tampon and is inserted, by a midwife or doctor, in the same way as an applicator-less tampon. The tape of the pessary can be felt at the opening of the vagina for easy removal. The pessary is intended to remain in place for 24 hours.

Propess® has a higher likelihood of causing hyperstimulation than Prostin® (see below) but has the advantage of being removable if this happens. Hyperstimulation is when the uterus contracts too frequently or contractions last too long, which can potentially lead to changes to the baby’s heart rate.

Prostin® tablet:

This is a low dose prostaglandin (3 mg dinoprostone) that is released into the vagina during an examination. It can be given every 6 hours. Prostin® is typically given once or twice, depending on if your cervix is ready for labour.

Risks (either approach)

- Hyperstimulation – the uterus has too many contractions and may need treating with medication to slow them down.

- Not always suitable for an induction if you do not want to stay overnight in hospital.

- Occasionally causes vaginal irritation or other side effects such as nausea and vomiting and back pain.

Benefits

- Less discomfort at insertion.

- More chance of spontaneous contractions.

- May reduce the chance of needing a caesarean or assisted birth.

Often, we use a combination of the 24-hour pessary and 1 to 2 of the 6 hourly tablets. You and your baby will be monitored regularly, before and after the insertion of the tablet or pessary then every 4 hours after, unless there is a need for more frequent monitoring.

What happens next?

When you have completed step 1 (either on the antenatal ward or as an outpatient) and your midwife or doctor has found that your cervix is open enough to have your waters broken, we aim to transfer you to labour ward as soon as safely possible. Delays in transfer do happen and when they do, we will try to keep you informed of the reason.

Sometimes your waters break, or established labour starts, earlier during the induction process. This might mean that you are ready to go to the labour ward before the ‘end’ of step 1 of the induction. This may be for additional pain relief beyond that available on the antenatal ward (for example regional anaesthesia such as epidural), because of concerns for your baby’s wellbeing or because your labour is progressing more quickly than anticipated.

It can be frustrating to see other women leaving the bay in labour when your contractions have not started. Everyone responds differently to the induction process. If your labour progresses more slowly, this does not mean you are doing anything wrong.

Step 2: Breaking your waters

This will take place on the labour ward during a vaginal examination and is known as ‘artificial rupture of membranes’ or ‘ARM’. A sterile plastic instrument will be used to make a small hole in the membranes around your baby. Your baby’s heart rate will be monitored for about 30 minutes using a CTG before the ARM is done.

You may be offered time after your water have been broken to move around and encourage contractions to start.

Most people having an ARM for their first baby will need a hormone drip to make labour start - 1 in every 7 women will labour after an ARM without needing the hormone drip. If you have had a baby in the last 10 years, then about 1 in every 3 or 4 women will labour without needing a hormone drip.

Step 3: Hormone drip

A hormone is given intravenously (IV) via a ‘drip’ (cannula) which will be inserted (by a midwife) into a vein in your hand or arm while you are in the labour ward.

Oxytocin is a hormone naturally produced in your body and helps to make your womb contract and open your cervix. Syntocinon is the manufactured version of oxytocin that is used to stimulate your contractions during the third step of the induction process.

While you are having the hormone via the drip, we advise monitoring your baby’s heart rate continuously. This can be done wirelessly so that you can move around and change position as you wish. Some movements or positions can interrupt the recording of your baby’s heartbeat so we will work with you to maintain safe mobility. It is not possible to use the birth pool or showers while having the oxytocin drip but your midwife will help you find comfortable positions.

The baby’s heart rate monitor (CTG) is also used to record how often you have contractions.

Your midwife will adjust the amount of oxytocin that you receive to produce contractions 3 to 4 times every 10 minutes, mimicking natural labour.

Everyone responds differently. For some people only a small amount of oxytocin is needed to begin having contractions while others need much higher doses. A small amount is given to start with and increased every 30 minutes to achieve a safe and effective rate of contractions. Therefore, the time taken from starting the hormone drip to having regular contractions will vary and may take several hours.

Sometimes too many contractions can occur and affect your baby’s heart rate. If this happens you may be asked to change your position (usually to lie on your left side) to improve the blood flow to your placenta. The rate of the oxytocin drip can be reduced or it may be temporarily stopped.

Your midwife or doctor will answer any questions you might have regarding the hormone drip and support you to make a decision that is right for you. If you choose not to have the hormone drip or delay starting it, it may mean that your labour could take longer.

If your waters have already been broken, then the longer the time between breaking your waters and having your baby can increase your baby’s chance of having an infection.

Outpatient IOL - spending time at home during an induction

Depending on the reason for your induction, you may be able to have the first stage of the induction (cervix preparation) in hospital as an outpatient and then go home once step 1 has been started. This is called an outpatient induction.

You must have another adult with you at home and a means of transport back to the hospital. If this is something that you would like to consider and it has not been offered, please ask your doctor or midwife.

Benefits

- Being in your home environment rather than in hospital.

- Research suggests that people cope with early labour better at home.

- People having an outpatient induction report a better birth experience than those remaining in hospital for the whole process.

What happens during an outpatient induction?

You will be advised to attend the Maternity Ward and have checks of the fluid around your baby and the monitoring of your baby’s heart rate (CTG). If these checks are normal, you will have either a Propess® pessary or Cook’s balloon inserted (depending on what you have discussed with your doctor). Your baby’s heart rate will be monitored for a further 30 minutes and your own general observations recorded. You will then be able to go home.

If you have had a Propess® pessary inserted, you will be advised to attend the hospital after 24 hours, unless you have concerns sooner.

If you have had a mechanical method of induction, you will be given a time to attend hospital, about 12 to 18 hours later.

It is important that you contact the maternity unit as soon as possible if:

- Your waters break.

- You have any bleeding.

- You are concerned about your baby’s movements.

- You have regular, painful contractions.

- You cannot pass urine.

- Your pessary falls out.

- You feel unwell or have any sudden onset of pain.

Can I still give birth at the Birth Centre?

You may be able to give birth at the Birth Centre if active labour starts during the first step of the induction process and you have no significant risk factors and there are no fetal wellbeing concerns. You can discuss this in advance with your doctor or midwife. If you do not meet the criteria, NICE recommends that you have your baby on a consultant-led labour ward.

How long does an induction take?

The length of induction is different for every person and depends on how ready the neck of womb is for birth. In general, it may take 2 to 5 days from the start of the induction for your baby to be born.

There may be delays in the IOL process as we need to confirm safe staffing availability and bed capacity before proceeding at each step of the induction process.

If there is a high level of activity across the Maternity Unit or pressure on bed capacity, we may delay starting your induction until it is safe to do so. You may be offered an alternative such as re-booking your induction for a different day (if appropriate) or electing to take your care to another hospital.

There may be a delay once your cervix has opened enough for your waters to be broken and you are waiting for a bed on labour ward for the next stage. Moving to the labour ward can only happen when there is both a room and a midwife available to look after you. The order in which people are transferred to the labour ward is based on an assessment of their whole clinical background and prioritisation of safety rather than just the length of time since admission.

It is impossible to predict how long delays may be. This is due to the labour ward being a high activity area accepting women who come in directly from home in spontaneous labour or with other critical conditions. While every effort to minimise delays are taken, when they do happen, we always aim to keep you fully informed while continuing to monitor both you and your baby’s health.

What to do on the day of induction

On the day of your planned induction, you will receive a phone call from the Maternity Ward when we have a bed and a midwife available. The call may come up as an unknown or withheld number. The call will not usually be before 11:00am but is likely to be before 8:00pm.

When you are admitted for your induction you will have your blood pressure, pulse, SATS and temperature checked. Your baby’s heartrate will be monitored using a CTG before the induction starts.

Your birth partner can be at your initial induction assessment and stay with you on the ward. They can also be with you when you are in the labour ward.

If you are staying in hospital on the antenatal ward for your induction, you will in a 4 bedded bay area with other birthing people, who may also be having an induction of labour. Once the induction has started, you are free to move around the ward and hospital area. We ask that you keep your midwife informed if you leave the ward.

You will be given a call bell to alert a member of staff if you need.

During your stay, please let your midwife know immediately if:

- You have any pain or tightening in your womb.

- Your waters break.

- You have any bleeding.

- You are concerned about your baby’s movements.

- You are unable to pass urine.

- Your Propess® or balloon falls out.

- You have any other symptoms or concerns.

What to bring with you into hospital

As induction can be a long process, please bring plenty of things to keep you comfortable and occupied while in the hospital.

Please bring your hospital bag with you (even if you are planning an outpatient induction and likely to go home afterwards). Can you also bring in all of your medications.

You will be given breakfast, lunch and dinner as well as water, tea and coffee while you are staying in hospital. You are welcome to bring in specific snacks or drinks.

The next steps if the induction does not work

If your cervix remains closed (not prepared for labour) and it is not possible to break your waters following a mechanical or hormonal approach in step 1 of the induction, your midwife and doctor will discuss your options with you.

Depending on your wishes and circumstances you may be offered:

- To stop the induction and try again after a break (the next day or later, if appropriate).

- An alternative induction approach.

- A caesarean delivery.

Further information

NHS UK

Website: www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/labour-and-birth/signs-of-labour/inducing-labour/

NICE - Inducing Labour

Website: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng207